I’ve wanted to share my thoughts about Canada, and the end of our tour, for the past few months. The hardest part about writing this post has been processing what “the end of our tour” even means. Although we stopped riding in late August, it took until at least October for me to feel that the trip was actually over, that I wasn’t about to pack up and ride away. Sorting through those feelings has been an ongoing project, but it finally feels like it’s time to put down those thoughts.

Our trip through Canada was like a geographically distributed, month-long, lovingly hosted dinner party. We usually only have the chance to visit Jim’s family in small increments – for a few days in the summer, or a week in the winter. This was our first chance in many years to connect with everyone in a more meaningful way, and to stay as long as we wished. In return, all of Jim’s family made us feel like loved and honored guests the whole time we were in Canada.

First, we rode to Ottawa, and spent two days with with Jim’s aunt, Karen. From Ottawa, we rode to Toronto, where we spent a week with Jim’s parents, and attended his cousin Hallie’s wedding. The wedding allowed us to see the entire paternal side of the family, as well as to meet Hallie’s fiancé and his family. After the wedding, our next stop was in Guelph, to stay with Jim’s grandparents, Pops and Blossom. Finally, we rode to Waterloo, staying with his uncle Mike and Mike’s partner Michelle, as well as my friend, Lexi. We also visited Jim’s grandmother, Judit, in Waterloo.

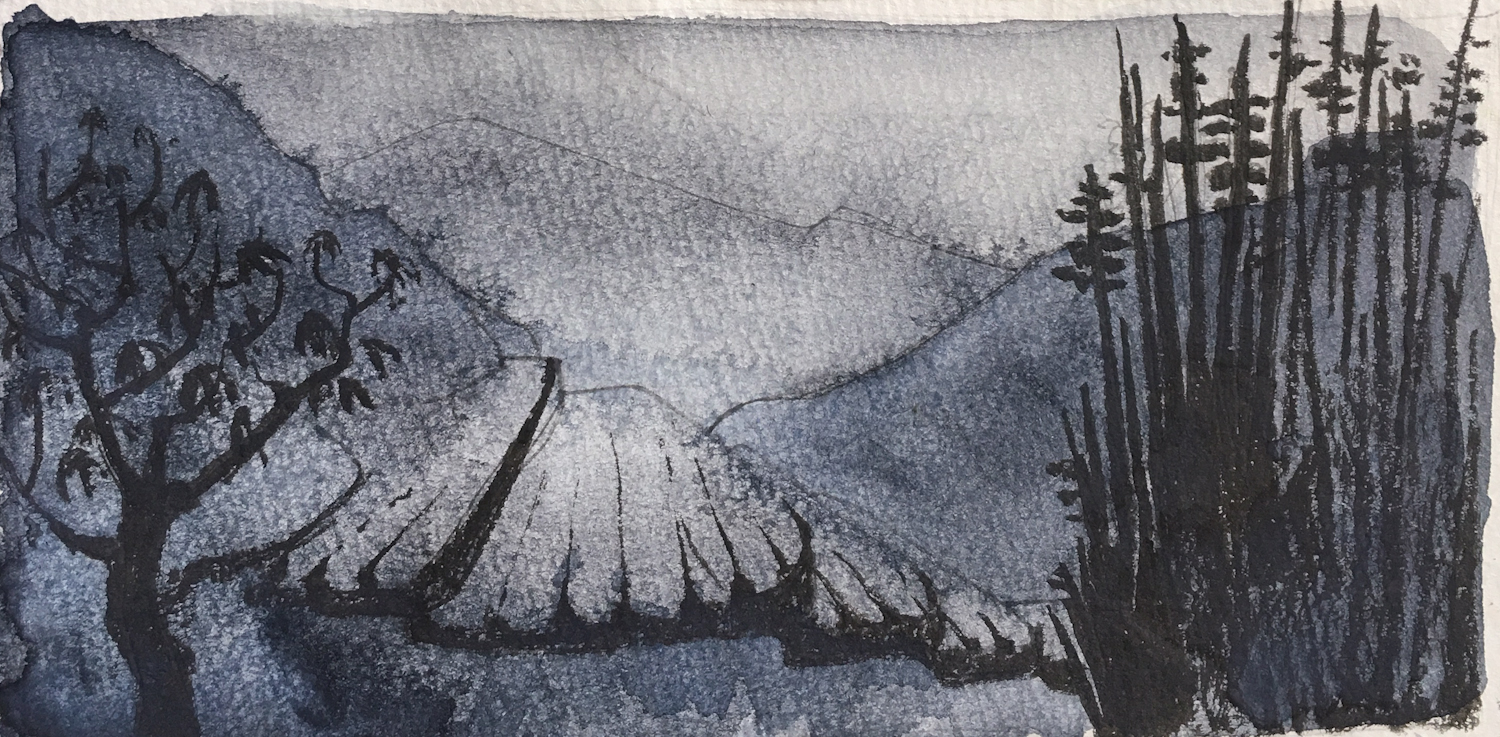

I thought the ride through Ontario would be easy for us. Unfortunately it turned out to be insufferably hot and humid, with a frequent headwind, and infrequent thunderstorms, which made riding frustrating and uncomfortable. Our route took us through rolling farmland and woods, with very little shade over the road. During the worst of it, we packed an insulated backpack with liters of water, soda and gatorade, and stopped to drink in every tiny shadow we found. We pushed ourselves harder than we should have, to spend less time on the road and more time with family.

Despite the weather, I did enjoy the chance to get to understand Canada a little better. It’s a huge country, but I was surprised that it felt linear – with America to our left and the Canadian shield to our right, we were biking through the only real populous strip of the country. Montreal, Ottawa and Toronto are major population centers, but development drops off rapidly once you leave the city. I had expected sprawling sub-developments and condominiums, but mostly I spent the week looking at wildflowers and lakes.

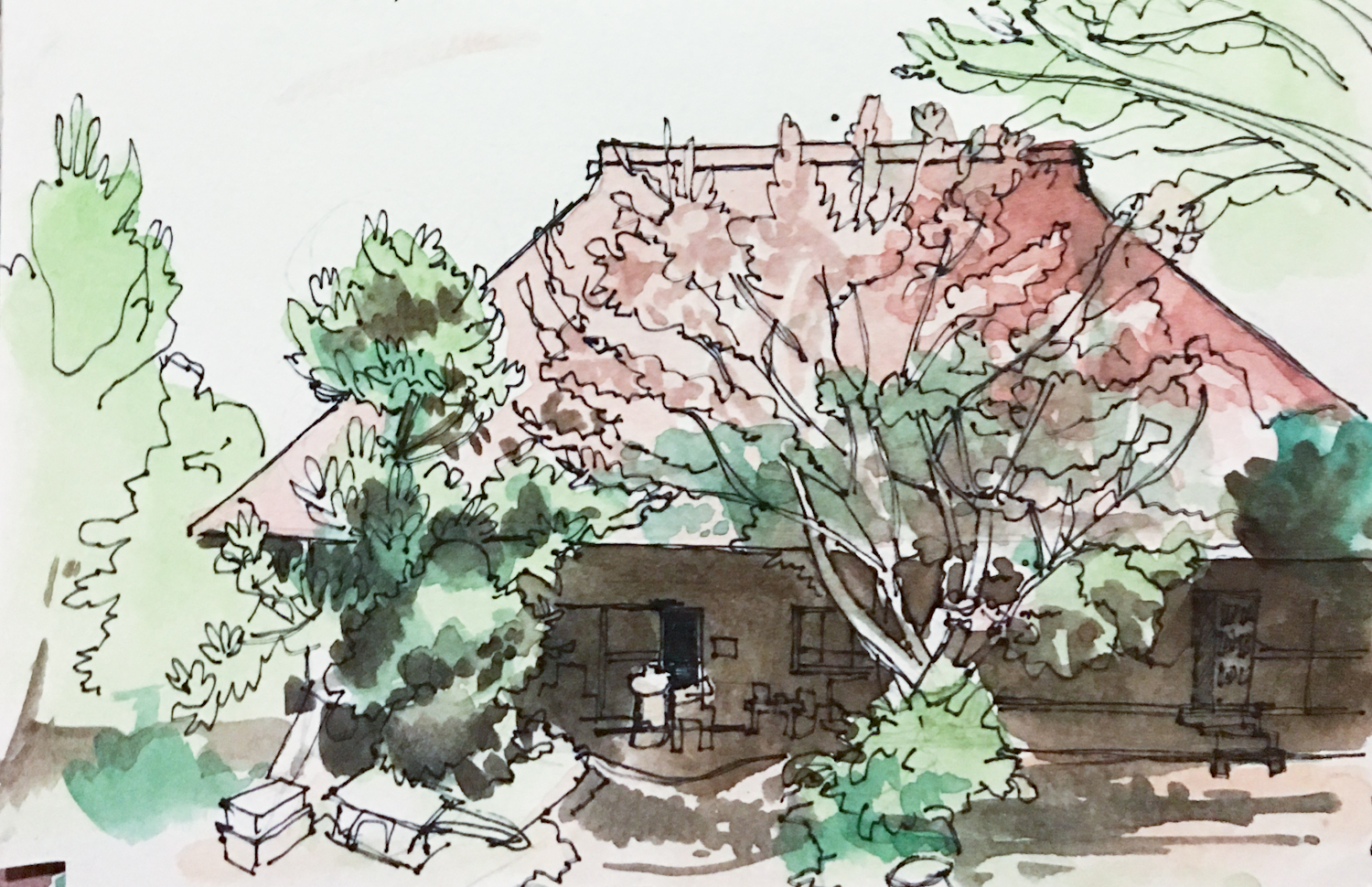

Whenever we passed through town, I also found that rural and suburban Ontario feel very different than rural and suburban America. I joked to everyone that “the American dream is alive and well in Canada” – there’s a particular sort of neighborhood with small, detached houses that seems to thrive in Ontario. It’s straight out of the white-picket-fence American subconscious.

At the end of our ride, we decided to return to the United States by turning back east and biking through Niagara. We planned our arrival to be on our first wedding anniversary. We booked a hotel looking over the Falls, and spent hours watching the water and talking about the last year. We used it as a chance to pause, and reflect on what this trip had been – certainly an incredible first year of marriage. The next day, we rode over the Rainbow Bridge into Buffalo, and the following morning took a sleeper train back to Boston.

After a year of indecision, we decided to move to Massachusetts at the end of our ride. We both missed Brooklyn, especially our friends there, but we had the feeling we needed to try something different. Eventually, we realized that the only way to choose between Boston and New York would be to try both – so we committed to a year in Boston. This decision was made simpler by the fact that many of our college friends, as well as my entire family, live in Massachusetts, which meant we had a surplus of spare rooms and couches to use while we resettled. We’re now renting a condo from two of our friends, who are away from Boston.

Being a stationary human has been an odd adjustment. There were so many silly things I was excited about when we stopped riding. I couldn’t wait to take my toothbrush out of its sticky travel case. I delighted in having a refrigerator – and a freezer! – with my own food in it. I wore all the warm, soft, bulky clothes I couldn’t carry on a bicycle – hoodies, and slippers, and sweatpants. I bought cut flowers and potted plants, just to own something green.

Not all of that transition has been fun – much of it has been very difficult. When I began this trip, touring quickly stopped feeling like a vacation, and more like a lifestyle choice. Ending that lifestyle, and transitioning back to being stationary, felt like a huge loss. With the trip over, where was I supposed to find purpose, goals, and novelty? Bike touring is neat and compact, like a microcosm of a fulfilling life. It has adventure, exercise, and obvious forward motion. None of these things are as simple to find when you’re not traveling, but they also seem more real, more in depth. I’m simultaneously skeptical of putting down roots, but trying hard to do so.

At her rehearsal dinner, Hallie pointed out to me that our trip was circular: “it started and ended with a wedding!” Since then, I’ve been seeing circles in everything. I ended up where I started – in Massachusetts, where I grew up. Jim has returned to his old job, we’ve retrieved some possessions from storage, and life has started to resume some kind of predictable rhythm. It’s hard to remember that the bike tour happened, that this time last year we were exploring the American south.

Even so, back where I began, I’m starting to understand that it’s me that’s changed. I keep discovering odd little differences in my experience and ways of thinking. It’s a little like coming back to a room and banging your shin into a coffee table that moved. I’ve found I’m far less frugal. I started cooking vegetarian food, by default, after I couldn’t handle a package of raw chicken at the grocery store. We donated suitcases of old clothes that I can’t remember why we kept. I suddenly crave the company of the public, in libraries, cafés, and on the subway. But I haven’t changed in some of the ways we like to imagine of travelers. I’ve rediscovered old habits, including some of the bad ones. I haven’t reached any kind of Instagram-worthy travel zen. I’m in better cardiovascular shape, but I certainly don’t look like an “after” photo.

What, then, now? I don’t think this was our last trip. I’m comforted by the knowledge that bike touring is something that’s always there – I could always throw some bags back on my bike, and leave for a day or an night or longer. That other life we experienced is still out there, and I can go back if I need to. I hope some day I will.

Until then, thank you to everyone for being a part of an amazing, unbelievable year.